Breast cancer is a complex illness with medical, emotional, and social dimensions. It remains one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers worldwide and a leading cause of cancer-related death among women in many regions. Over recent decades, advances in screening, diagnostic imaging, pathology, systemic therapies, surgical care, and supportive services have improved survival and quality of life for many people. Nonetheless, breast cancer continues to affect millions of lives each year, and disparities in access to care mean that outcomes vary widely by geography, socioeconomic status, and health system resources.

This guide is intended to provide a comprehensive, accessible overview of breast cancer for patients, caregivers, and anyone who wants to learn practical, evidence-informed information. We’ll cover basic breast anatomy and the biology of cancer, the main types and how they’re classified, risk factors and prevention strategies, symptoms and early warning signs, screening and diagnostic approaches, staging and prognosis, treatment options and their side effects, considerations for survivorship, and resources you can use. This is general information — for personal medical advice, always consult your healthcare team.

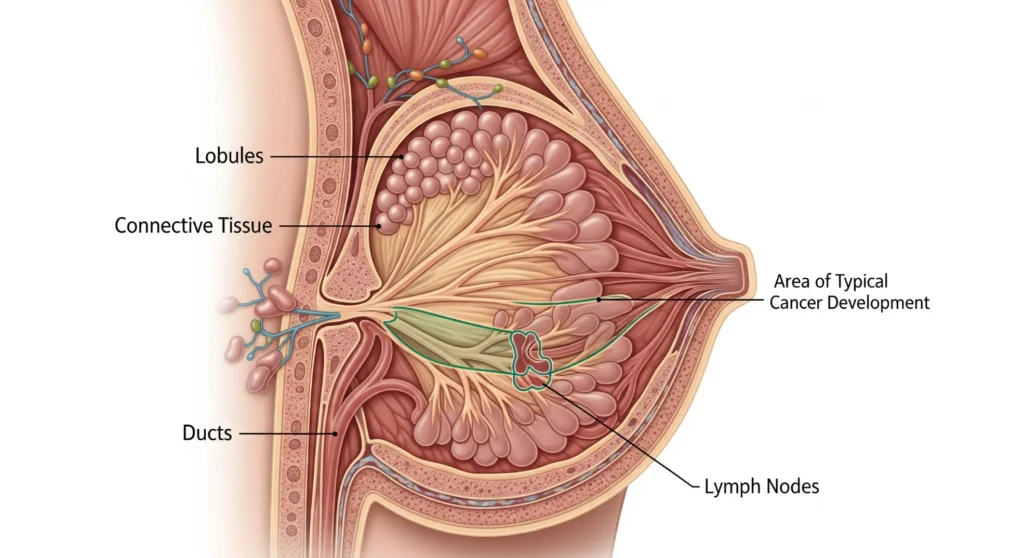

Understanding breast anatomy and how cancer develops

A working understanding of breast structure helps explain how and where cancer arises. The breast is made up of glandular tissue (lobules that produce milk) connected to ducts (tubes that carry milk to the nipple), embedded in fatty and connective tissue that gives the breast its shape. Lymphatic vessels drain fluid from the breast into regional lymph nodes — most importantly nodes in the axilla (armpit) and near the breastbone. Cancer most commonly starts in the cells lining the ducts (ductal cancers) or the lobules (lobular cancers). When breast cells accumulate genetic and other abnormalities that allow them to grow unchecked, a tumor can form. If left untreated, cancer cells can invade surrounding tissue and spread via the lymphatics or bloodstream to distant organs such as bone, liver, lungs, or brain.

Pathologists classify tumors by their microscopic appearance (histology) and by molecular features. The most important biomarkers are estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2. Tumors that express ER and/or PR often respond to hormone-blocking therapies. HER2-positive tumors often respond to targeted anti-HER2 drugs. Tumors without ER, PR, or HER2 expression are labeled triple-negative and require different systemic approaches.

Major types of breast cancer

Breast cancer is heterogeneous. Key categories include:

- Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): non-invasive, confined to ducts, often detected by mammography. DCIS is usually treatable and may be cured with local therapy.

- Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC): the most common invasive type; begins in ducts and invades surrounding tissue.

- Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC): arises in the lobules; can be harder to detect on imaging and may present as subtle thickening.

- HER2-positive cancers: overexpress the HER2 protein; historically more aggressive but now treatable with targeted therapies that markedly improve outcomes.

- Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC): lacks ER, PR, and HER2 expression; more common in younger patients and certain populations and usually treated with chemotherapy and increasingly with targeted or immune-based options.

- Inflammatory breast cancer: rare but aggressive; the breast may appear red, swollen, and warm rather than having a discrete lump.

Within these categories, genomic assays that analyze patterns of gene expression can further stratify tumors and help guide treatment choices.

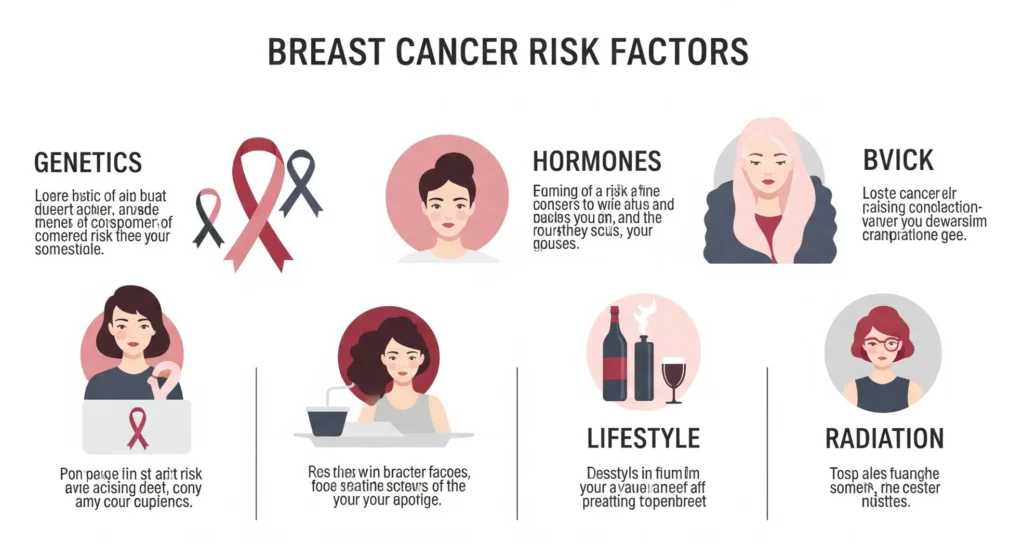

Who is at risk: causes and risk factors

Breast cancer risk arises from many interacting factors:

- Age: the single strongest risk factor; incidence increases with age.

- Reproductive history and hormones: early menarche, late menopause, not having children or having first child later in life slightly raise risk; postmenopausal hormone therapy can increase risk depending on type and duration.

- Genetics: inherited mutations in genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 confer substantially higher lifetime risks; other genes (PALB2, CHEK2, TP53, ATM) also contribute. Most breast cancers, however, occur in people without a known inherited mutation.

- Lifestyle: alcohol intake increases risk in a dose-dependent fashion; obesity after menopause increases risk; regular physical activity reduces risk.

- Radiation exposure: high-dose chest radiation at a young age raises risk (for example, prior therapeutic radiation).

- Other factors: breast density on mammography is a risk factor and can make detection more difficult.

Geography and access to care shape observed incidence and outcomes: countries with widespread screening report more early-stage diagnoses and better survival, while regions with limited access to screening and therapy experience higher mortality.

Symptoms and early warning signs

Many breast cancers are found by screening mammography before symptoms appear, which is why screening programs matter. Still, be alert to changes and seek evaluation promptly if you notice:

- A new lump or persistent area of thickening in the breast or underarm.

- Changes in breast size, shape, or symmetry.

- Skin changes over the breast such as dimpling, puckering, redness, or an “orange peel” texture (peau d’orange).

- Nipple changes such as retraction, inversion (new), or unusual discharge (particularly if bloody).

- Persistent local pain in a specific area of the breast (most breast pain is not caused by cancer, but persistent focal pain should be checked).

Not every change indicates cancer, but timely evaluation by a clinician is essential to rule out serious causes.

Screening: when and how

Screening aims to detect cancers at an early, treatable stage. Recommendations vary by national guidelines and individual risk:

- Mammography is the primary screening tool. Digital mammography improves detection in many settings.

- Breast MRI is used in high-risk individuals (for example, carriers of BRCA mutations) because it is more sensitive than mammography.

- Ultrasound is often used as an adjunct in women with dense breast tissue or to evaluate a mammographic abnormality.

- Clinical breast exam and breast self-awareness have roles but are not substitutes for imaging-based screening.

Screening intervals and starting ages differ across organizations; decisions should be personalized based on age, risk factors, and preferences. Individuals at high inherited risk commonly undergo enhanced surveillance with earlier and more frequent imaging.

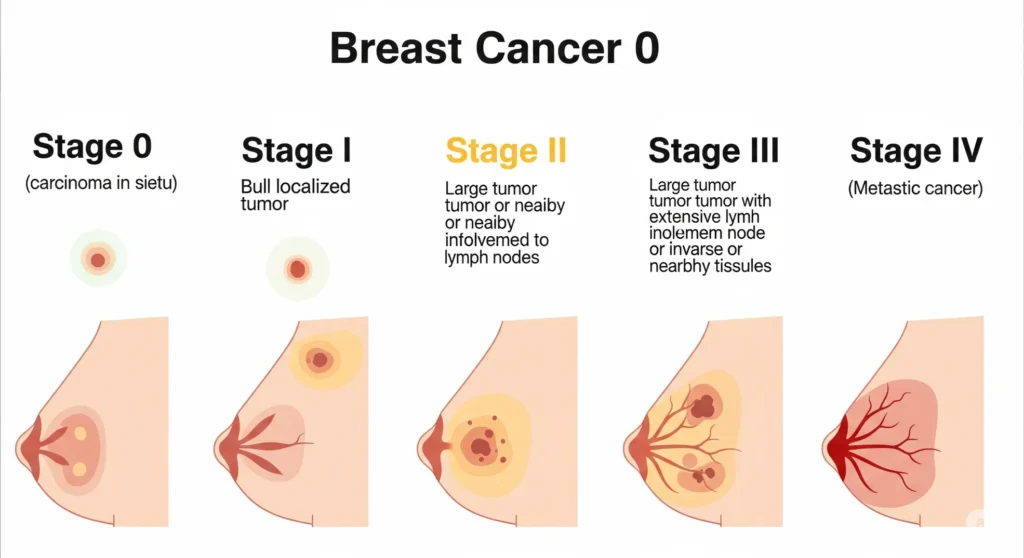

Diagnosis and staging

When screening or symptoms raise concern, diagnostic imaging and tissue sampling follow:

- Diagnostic mammography and targeted ultrasound focus on the suspicious area.

- Image-guided biopsy (core needle biopsy) obtains tissue for pathological diagnosis and biomarker testing.

- Pathology determines the tumor type, grade, and receptor/HER2 status; modern reports often include additional molecular information to guide therapy.

Staging uses tumor size (T), regional lymph node involvement (N), and distant metastasis (M). Modern staging systems also incorporate tumor biomarkers to refine prognosis and treatment planning. Early-stage cancers confined to the breast and regional nodes have the best prognosis; metastatic disease is treated with systemic therapies and palliative measures to control symptoms.

Treatment overview: individualized, multidisciplinary care

Treatment plans are tailored to tumor biology, stage, patient health, and personal priorities. A multidisciplinary team typically includes surgical oncology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, nursing, pathology, radiology, genetics, rehabilitation, and psychosocial support.

Major treatment modalities:

- Surgery: lumpectomy (breast-conserving surgery) or mastectomy; sentinel lymph node biopsy guides axillary management.

- Radiation therapy: typically follows breast-conserving surgery and is used in selected mastectomy cases to reduce local recurrence. Modern radiation techniques limit exposure to surrounding tissues.

- Systemic therapy treats disease throughout the body and may be delivered before surgery (neoadjuvant) to shrink tumors or after surgery (adjuvant) to reduce recurrence:

- Chemotherapy — cytotoxic drugs that target rapidly dividing cells.

- Hormone (endocrine) therapy — for ER/PR-positive cancers (e.g., tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors).

- Targeted therapy — drugs directed at specific molecular features, such as anti-HER2 agents (e.g., trastuzumab and newer antibody-drug conjugates).

- Immunotherapy — immune checkpoint inhibitors are active in some contexts (for example, certain triple-negative cancers) and are an expanding area of research.

Treatment sequencing and combination depend on goals: cure, control, or palliation, and on tumor responsiveness.

Surgery and reconstruction

Surgical choices balance oncologic safety and cosmetic outcomes. Lumpectomy plus radiation achieves cancer control comparable to mastectomy for many early-stage tumors. Mastectomy may be recommended for larger or multicentric tumors, or chosen for patient preference. Reconstruction options include implants or autologous tissue flaps and can be performed immediately or delayed depending on clinical circumstances. Sentinel lymph node biopsy minimizes morbidity compared with full axillary dissection; lymphedema risk is reduced but not eliminated.

Systemic therapies in depth

Systemic therapy selection uses tumor biology:

- Hormone receptor–positive disease benefits from hormonal therapies that block estrogen’s effect (tamoxifen) or reduce estrogen production (aromatase inhibitors). Extended endocrine therapy beyond five years may be appropriate in selected cases.

- HER2-positive disease responded dramatically to HER2-targeted agents; combinations of chemotherapy and targeted therapy have changed survival. Newer antibody-drug conjugates deliver cytotoxic payloads directly to HER2-expressing cells.

- Triple-negative disease is heterogeneous; chemotherapy remains essential in many cases, while immune therapies and targeted agents are emerging for specific subgroups.

- Ongoing trials continue to refine the role, timing, and duration of systemic agents, as well as combinations that may improve outcomes with manageable toxicity.

Side effects, drug interactions, cardiac monitoring (for select agents), and fertility considerations are integrated into treatment planning.

Managing side effects and supportive care

Treatments bring potential side effects that can be managed proactively:

- Chemotherapy-related: nausea, fatigue, hair loss, neutropenia, neuropathy — preventable and treatable with antiemetics, growth factors, dose modifications, and supportive therapies.

- Hormonal therapy: hot flashes, bone density loss (monitor with DEXA and use bone-preserving strategies), joint symptoms.

- Radiation: skin irritation, fatigue, and rarely late tissue fibrosis; modern techniques reduce risks.

- Fertility: discuss preservation options before gonadotoxic therapy; fertility counseling is essential for young patients.

- Lymphedema: early education, physical therapy, and compression can prevent or control swelling.

- Psychosocial care: counseling, peer groups, and psychiatric support improve coping and quality of life.

Palliative and rehabilitation services aim to maintain function and independence.

Prevention, risk reduction, and healthy living

Not all breast cancers are preventable, but risk can be lowered with practical measures:

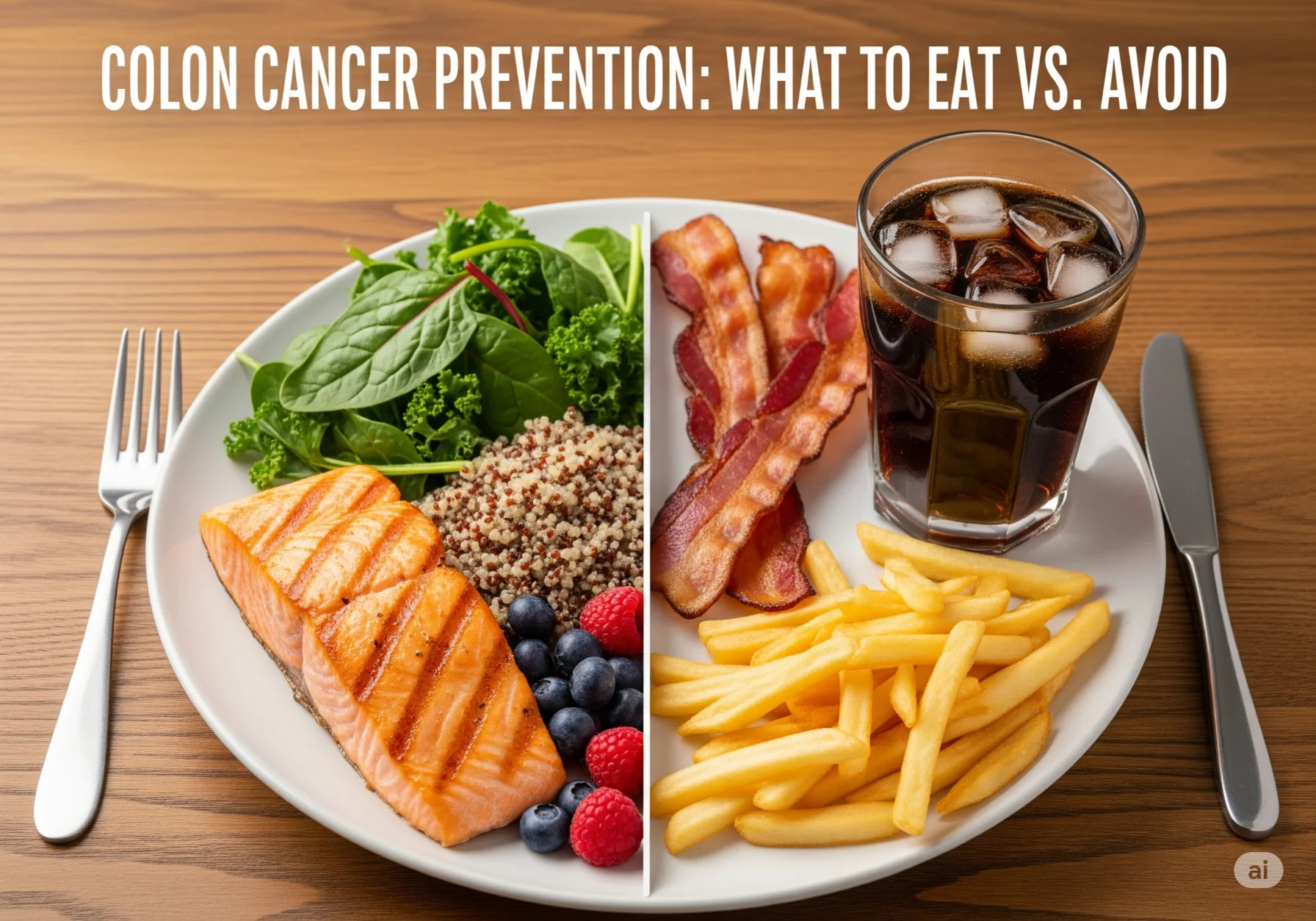

- Limit alcohol and maintain a healthy weight, especially after menopause.

- Regular exercise is protective. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity weekly, plus strength training.

- Consider breastfeeding when possible; it provides modest protection.

- Avoid tobacco and minimize unnecessary medical radiation exposure when possible.

- High-risk options: for individuals with high-penetrance mutations (e.g., BRCA1/2), enhanced surveillance, chemoprevention, or risk-reducing surgery may be discussed with specialists.

Shared decision-making with clinicians helps match prevention approaches to individual risk and values.

Survivorship, emotional impact, and long-term follow-up

Survivorship care addresses ongoing surveillance for recurrence, management of late treatment effects, lifestyle counseling, and psychosocial needs. Many survivors report fear of recurrence, body image concerns, and changes in sexual health or employment. Peer support, counseling, rehabilitation, and occupational resources help patients return to meaningful activities. Regular follow-up visits include physical exams and, in most cases, annual or routine imaging guided by oncology recommendations. Coordination between oncology, primary care, and other specialists ensures ongoing preventive care and management of comorbid conditions.

Special situations: men, pregnancy, and younger patients

- Men can get breast cancer—rarely but importantly. Presentation may include a painless lump or nipple changes; delays in recognition are common.

- Pregnancy-associated breast cancer requires specialized multidisciplinary care balancing maternal therapy and fetal safety. Some treatments can be given safely during pregnancy, but planning is complex.

- Younger patients face unique concerns: fertility preservation, early menopause, long-term cardiovascular and bone health effects, and psychosocial challenges.

Disparities, advocacy, and community action

Access to screening, prompt diagnosis, and high-quality treatment heavily influence outcomes. Advocacy and public policy that expand access to care, address social determinants of health, and fund research are essential. Community-driven efforts — mobile screening units, patient navigation programs, culturally tailored education, and financial assistance programs — make a measurable difference in earlier detection and improved survival.

Practical takeaways and a checklist

- Learn the recommended screening approach for your age and risk level.

- Report any persistent breast changes promptly.

- Discuss family history with a clinician and consider genetic counseling when appropriate.

- Adopt healthy lifestyle habits that lower cancer risk and support recovery.

- Ask about fertility preservation if you plan future pregnancy and will receive treatments that may affect fertility.

- Seek care from a multidisciplinary breast team when possible and inquire about clinical trials if standard options are limited.

Conclusion

Breast cancer is a multifaceted condition, but advances in early detection and personalized therapy mean many people live long, healthy lives after diagnosis. Knowledge, timely evaluation of symptoms, informed screening, individualized treatment, and strong supportive care are central to improved outcomes. Equitable access to these services remains a global priority. If you or a loved one faces breast cancer, reach out to trusted healthcare providers and support organizations: you don’t have to navigate it alone.

F micle

very helpful article, thank you purepath health ❤